In February 2021, President Xi Jinping of China proudly declared the eradication of extreme poverty in his country – and this is indeed a historic achievement for the world’s most populous nation, with centuries of endemic poverty, inequalities and feudal injustices to deal with – but how far the rest of the world will be able to emulate China in this regard, is a moot point.

The very first two goals of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals are in fact:

- End poverty in all its forms everywhere

- End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture

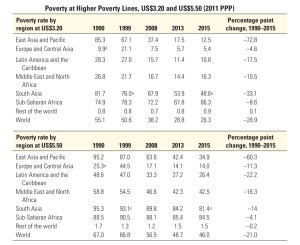

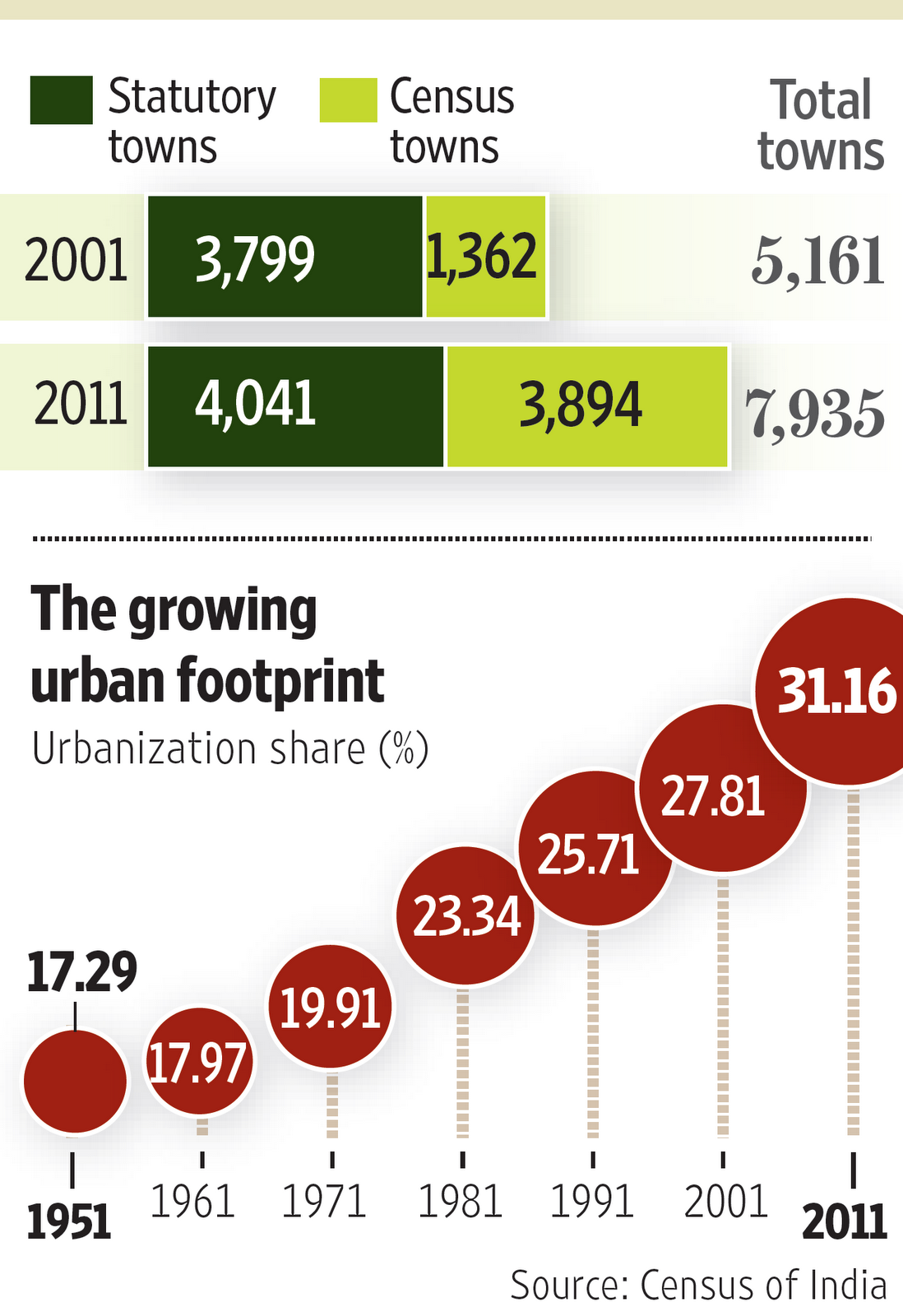

However, with the fallout from a year of pandemics and disasters still being measured, it is extremely unlikely that the governments in vulnerable areas like South Asia will be able to achieve these goals on schedule. And with some of the most populous nations on the planet, the figures from South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh et al) can affect global targets drastically.

Meantime, civil society around the world has been moved by the plight of the suffering millions on an unprecedented scale, and every country, city, community is looking for ways in which the better-off (especially the young) can do something to ‘give back to society’.

Unfortunately, many of these well-intentioned efforts remain unorganized, making them prone to opportunistic politicization, or else individual inspiration drips away as a trickle into the empty desert sand – making no lasting impact on the lives of their intended beneficiaries.

I have noticed that one of the most bookmarked posts on this website is Dimensions of Urban Poverty, and always believed that it was something students googled most often, perhaps for a class assignment or as an introduction to their own writings on urban poverty. Then I got a request from somebody in India who felt inspired by my various posts on poverty and wanted my help in designing certain voluntary actions because they ‘wanted to give back something to society’ by working with deprived communities in their areas. As the viewership of this blog has now hit 155 countries, I realized that people across the world may be looking for some framework to hang their good intentions on, so why don’t I attempt a simple generic template for voluntary action among poor communities, which could be customized to local needs and used across the world?

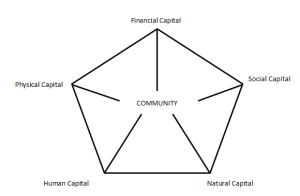

This framework draws largely on the well-known Sustainable Livelihoods Framework, where sustainability is achieved by building up 5 types of ASSETS or CAPITAL: Human, Financial, Physical, Social and Natural.

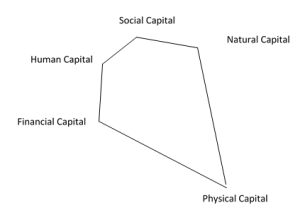

The underlying assumption is that as we build up each of these capitals, the LIVELIHOOD POLYGON of an individual or community becomes progressively enlarged, so that the individual or community gradually gets lifted out of ABSOLUTE and eventually, RELATIVE poverty.

The SL Framework defines five types of Capital Assets. These are:

Unfortunately, most government programmes tend to focus on just one type of capital/asset, thereby greatly shrinking the options available to the poor. For example, slum upgradation programmes in India concentrate on providing only physical infrastructure like internal roads, storm drains, public water and sanitation, and neglect the growth of human capital through better health and education services. This results in a skewed livelihood polygon with a much smaller area of opportunity for the individual and community.

This is where Voluntary Action can fill the interstices, as it were, and help in building up all 5 types of ‘capital’ in a poor community so that the overall livelihood polygon can be expanded.

Thus, FINANCIAL CAPITAL can be greatly augmented through:

- Providing a place for a cooperative store / fair price shop to be run by the community

- Starting kitchen gardens

- Installing metered electricity connections in each household

- Forming women’s Self-Help Groups and Thrift Societies

- Setting up labour cooperatives

- Providing vocational training geared to local handicrafts / industry

- Helping artisans to adopt modern design, manufacture, and management practices to make their traditional goods attractive to the modern consumer

- Facilitating the listing of local businesses on e-retail sites like Amazon

NATURAL CAPITAL can be enhanced by easy ‘doables’ like:

- Providing a playground for children near their homes

- Initiating participatory activities for improving community environment and sanitation

- Providing the means for rainwater harvesting, localized garbage treatment and recycling

- Developing sources of renewable energy like wind or solar power, depending on the geography and feasibility

- Ensuring a clean and safe drinking water supply in every home

The growth of HUMAN CAPITAL in a community is a combination of sound health, education, skill development and capacity to work. All countries have numerous human development programmes either initiated by donor agencies, through NGOs, or undertaken by Governments themselves. Voluntary agencies can run their own micro-programmes within communities to enhance their Human Capital, such as:

- Holding camps for regular antenatal and post-natal check-ups including counselling and testing for HIV/AIDS and STD

- Conducting nutrition checks on under-5 children on a monthly basis

- Mass testing for communicable diseases

- Organising immunization camps

- Running training camps in various sports for children

- Running a mobile clinic scheme for a cluster of poor communities with help from local corporates under their Corporate Social Responsibility Programmes

- Improving housing and sanitation

- Running ‘pavement’ schools and night classes for school dropouts / child labourers

- Mobilising Women’s Self Help Groups for running awareness campaigns against drug addiction, alcoholism, domestic violence, underage marriages, teen pregnancies etc, and monitoring school attendance to prevent drop outs

PHYSICAL CAPITAL because of the high capital outlay is best left to the local authority, though voluntary agencies and self-help groups can play a role in ensuring that this expensive asset is well taken care of, not misused or allowed to fall into disrepair.

Where there is a government funded Housing Scheme for the poor, volunteers can play a major role in arranging proper legal advice to the beneficiaries especially in the matter of land ownership, title, mortgage and taxation which are most nebulous in most developing countries and prevent the assets of the poor from becoming fungible and tradeable – so that the poor remain poor in perpetuity.

It is often said that SOCIAL CAPITAL is the only wealth of the poor, given the vast array of caste, clan, ethnic, linguistic, tribal and kinship networks in rural and tribal areas around the world. These ties, however, are the first casualty, when the rural poor migrate to cities. However, it is possible through development interventions to build new networks and support systems – the most obvious examples being Self Help Groups, Thrift Societies, and Workers’ Cooperatives. Group activities like literacy drives, religious festivals, carnivals, mass immunization campaigns, and nutritional assessment camps are also instrumental in cementing community bonds, besides helping with human capital growth.

Working with the urban poor needs an understanding of the underlying social and political reality and the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework is the most practical template to apply.