As we celebrate another Independence Day in India, there will be a lot of chest thumping about the steadily growing GDP, reaching a record $3.75 trillion in 2023.

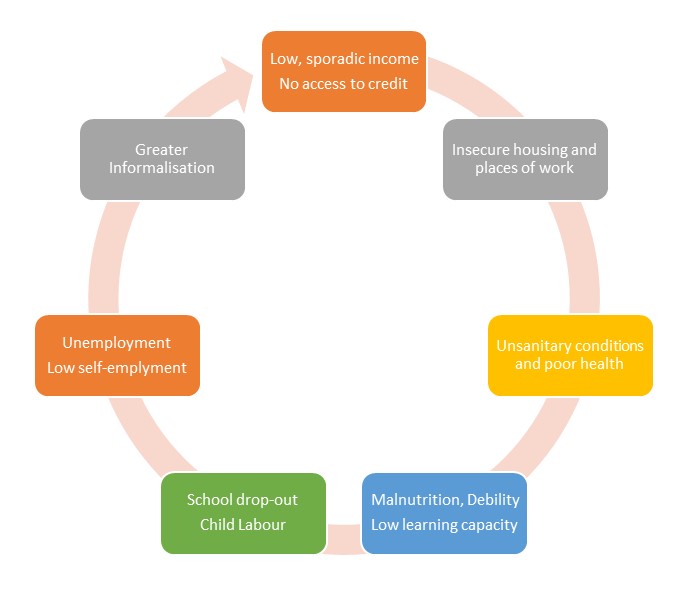

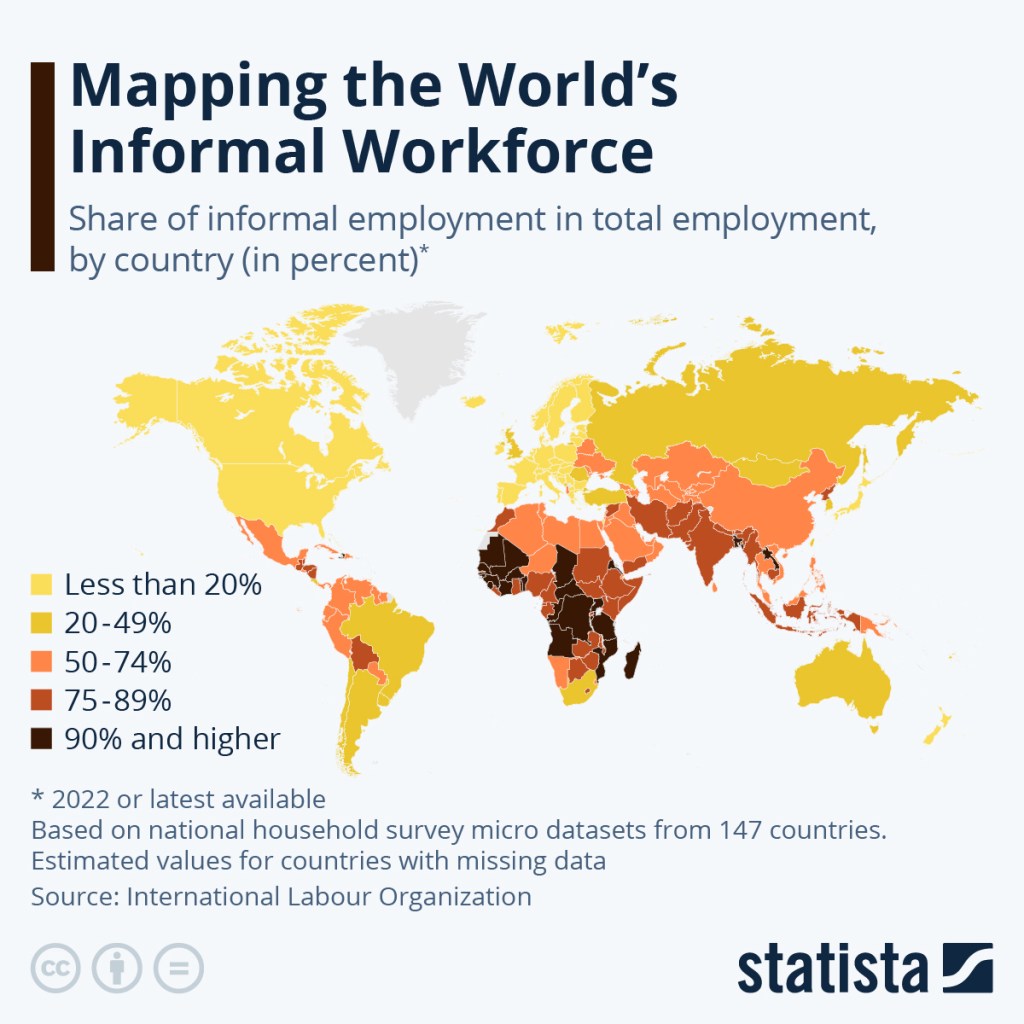

However, the flip side is that the benefits of this economic growth are not reaching 75-85% of the common people, trapped as they are in India’s infernal informal sector.

As a consequence:

- The poverty rate in India has remained high, at 21.9% on the Multidimensional Poverty Index, and the number of people living in poverty is not declining

- India’s Human Development Index has not improved significantly in recent years. In 2014, it was 0.629, and in 2022, it was 0.631 and the country ranks at 135/188

- Levels of Inequality are amongst the highest in the world. The richest 1% of Indians control more than 20% of the country’s wealth, while the poorest 50% of Indians control less than 10% of the wealth. The increasing inequality in India is not just of income and resources but also of opportunity, and as caste, class and birth continue to eclipse the opportunities available to an individual, the poor continue to remain poor as will their children and grandchildren. And continuing informalization will only deepen the divide between those who can and those who cannot

The social effects of the growing informalisation of the economy are already visible:

- Vast numbers of unemployed and underemployed youth are just waiting to be exploited by the rich and powerful to ignite an incident here, a rampage there, resulting in an increasingly unstable law and order situation

- The decline in India’s manufacturing capabilities continues, where the trade deficit keeps inexorably rising, and domestic consumption is relegated to shoddy products manufactured in sweatshops in back alleys with no regard for quality assurance or labour welfare – leading to greater exploitation of the working class

- The growing fatalism among the poor is very noticeable today, along with the total annihilation of protest movements, because the formal sector trade unions have been systematically eliminated following liberalisation

- The increasing privatisation of primary, secondary and tertiary education and health care has eroded the very core of a welfare state that Nehruji evoked in his famous ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech on 15 August 1947. This has not only nullified India’s demographic dividend, but will adversely affect the quality of its human resources for generations to come.

- The total politicisation of society, where even the most basic of human rights are bestowed as a ‘gift’ by the rulers and the subsequent subsidisation of basic needs, which creates the ‘dependency culture’ so noticeable in the declining years of all great powers. Moreover, workers in the informal sector are denied a feeling of self-worth and self-esteem and their only identity becomes an anonymous number in an indifferent identity system like Aadhar – which is at best a way to procure meagre benefits from an uncaring government, not a ticket to claim their rights as proud citizens of this country

* * *

The time has come this Fifteenth Day of August to revert to the original meaning of ‘Azadi’, which is not just independence but FREEDOM – a freedom from subservience, apathy, anomie, poverty, illiteracy, illness and the shackles of a burdensome past of grudge and grievance.

Happy Freedom Day to all!

Related: