First published on 8 February 2015

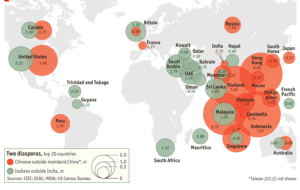

I started this blog to counter the current Indian Government’s proclivity for mega pronouncements without thinking through the implications. The latest buzz phrase is ‘Make in India’. But make in India for whom? The domestic consumer or the European and American consumer, where India hopes to replace China as the key provider of the basic essentials of life?

Update 1:

Despite various bans and boycotts imposed by the Government of India on Chinese goods following a border clash, Indian imports from China in 2021 reached a whopping $97.5 Billion, a 30% rise from 2019. Moreover, these imports are largely ‘manufactured’ goods like electrical and mechanical machinery, auto components, pharmaceutical ingredients, and medical supplies like oxygen concentrators and PPEs.

So much for ‘Make in India’…

India is also not able to compete in export markets for manufactured goods because of its relatively poor infrastructure and tedious red tape, widespread petty corruption, an ill-educated workforce (by international standards) and the prevalence of child labour and forced labour somewhere in every corporate supply chain, which creates a very negative image of the country in the minds of the western consumer, who is tech-savvy, globally connected, well-informed and increasingly believes in conscious consumerism.

Update 2:

Need for Regulating Supply Chains

In the early years of this century, the movements for ethical supply chain management gathered momentum, and every time there was a furore in the western media about environmental damage, animal experimentation, poor labour practices, or unsafe working conditions anywhere down a long and trailing multinational supply chain, the most high-profile retailer bore the brunt of boycotts and protests. This was unacceptable in economic terms and extremely expensive in transnational legal terms, and so a global standard had to be put in place to assure ethical supply chain management.

The best known of these is the SA8000 initiated by Social Accountability International, a US-based non-profit. The SA8000 looks at human rights in the workplace, worker safety, child labour and forced labour and other issues, based upon ILO guidelines, the UN Declaration of Human Rights, and the UNICEF Convention on Rights of the Child.

Its 9 principles for certifying a business as SA8000 compliant are:

- Child Labour: No child labour; remediation of any child found working

- Forced Labour: No forced labour; no lodging of deposits or identity papers at employers or outside recruiters; no trafficking

- Health and Safety: Safe and healthy work environment; system to detect and prevent threats to health and safety; regular health and safety worker training; access to clean toilet facilities and potable water

- Freedom of Association and Right to Collective Bargaining: All personnel have the right to form and join trades unions and bargain collectively; where these rights are restricted under law, the company shall allow workers to freely elect their own representatives

- Discrimination: No discrimination based on gender, race, caste, origin, religion, disability, sexual orientation, marital status, family responsibilities, trade union or political affiliation, or age; no sexual harassment

- Discipline: No corporal punishment, mental or physical coercion or verbal abuse

- Working Hours: Compliant with applicable law, but, in any event, no more than 48 hours per week with at least one day off following every six consecutive days or work; voluntary overtime paid at a premium rate and not to exceed 12 hours per week; overtime may be mandatory if part of a collective bargaining agreement

- Remuneration: Wages paid for a standard work week must meet legal and industry standards and be sufficient to meet the basic needs of workers and their families and to provide some discretionary income

- Management Systems: To earn and sustain certification, facilities must go beyond simple compliance to integrate the requirements into documented management systems and into their supply chain, including complaints response, workplace dialogue, and stakeholder engagement.

Compliance with SA8000 includes compliance with ILO conventions, local and national law, openness to worker concerns, and a commitment to continuous improvement. Research I undertook in 2012 threw up the following interesting facts about the 614 SA8000 compliant businesses in India at that time:

- The most common businesses opting for SA 8000 were small and medium enterprises, (the reasoning is that large, heavy manufacturing businesses already have the statutory framework in place in compliance with the existing labour legislation in India, and therefore do not require an SA 8000 type of certification for their international trade activity).

- Most of the SA 8000 certified Indian businesses are essentially part of the supply chain of large multi-national retailers, who insist on such certification, while domestic retailers seldom do

- Most of the SA 8000 certified Indian businesses manufacture consumer nondurables like apparel, textiles, footwear, processed foods, leather and sports goods

- Most of the SA 8000 certified Indian businesses are likely to be located in the States with niche manufacturing small and medium sector enterprises, like Tamil Nadu, where the overwhelming number of SA8000 compliant companies were in Tirupur, a cotton apparel town, sometimes called the ‘ganji’ or capital of the world for its exclusive production of men’s vests and T-shirts.

However, just 600-700 ‘ethical’ businesses in a country with hundreds of thousands of small and medium enterprises is indeed laughable, and this ‘tokenism’ in the name of ethical supply chains by the manufacturing sector is bound to take its toll in the international market, where the conscious consumer is now king.

Whatever claims of equitable work conditions are made by corporate India, the sad fact is that India’s image abroad has steadily declined as it continues its downward slide in various international rankings like the World Hunger Index and the World Press Freedom Index; besides the negative press it gets abroad for its growing communalism, casteism, curtailment of dissent, and treatment of protesters.

The aftermath of the COVID19 pandemic too has added to India’s woes as huge masses of rural children have dropped out of the education system into forced and child labour, and general poverty, unemployment, informalisation and inequality have reached frightening levels.

———————————————————————————————–

Thus, before proclaiming grandiose schemes like ‘Make in India’, perhaps the Government should overcome its aversion to ‘leftist’ ideals of a rights-based approach to human development – especially, education, vocational training, and public health. This was the path so successfully followed by Japan, Singapore, South Korea and China. Let India not go down in history as the country which so carelessly threw away its priceless demographic dividend.