Clichés about Indian cities abound – the skyscrapers of the rich surrounded by the squalor of slums, the overcrowded public transport, the stray cows at the crossroads, the piles of garbage, the algae infested waterways, the polluted and unbreathable air… and successive governments have simply not had the time (because rural poverty required attention immediately after Independence) nor the inclination (because urban India has just 31% of the vote) to do anything about India’s dead and dying cities.

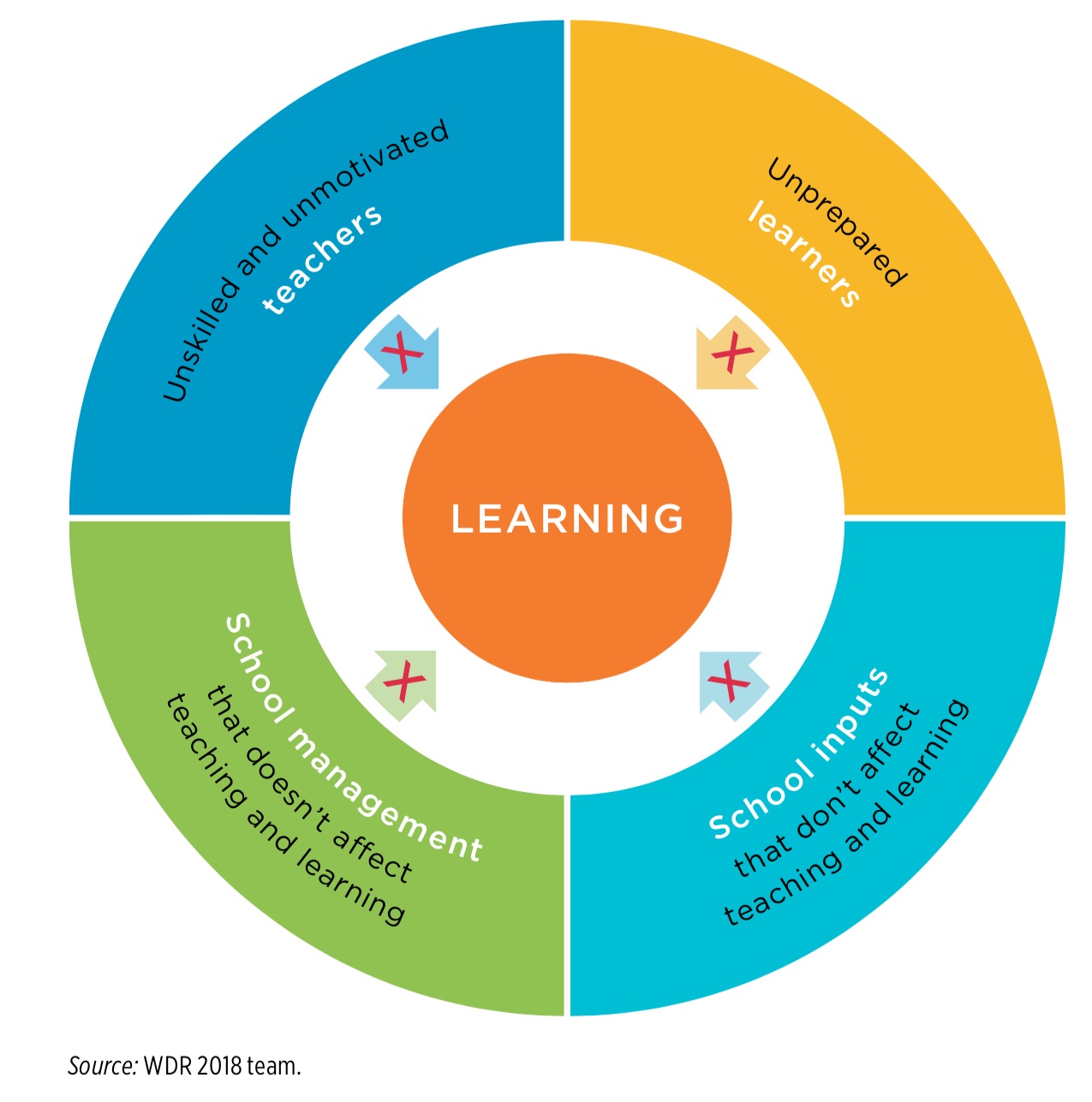

To make matters worse, Indian urban planning has always been trapped in something of a time warp, still true to its British parentage, while countries like South Korea, Singapore and China have surged ahead and shown the world how millions of urban dwellers can live in cities that work, and are still people-friendly.

Like all the laws governing Indian cities today, the planning laws too originated under British rule in the Bombay Town Planning Act of 1915, and it is quite understandable that the provisions of this law all hark back to ‘the green and pleasant land’ the law makers had left behind, and wished to recreate in India. Never mind that Britain had solved its population problems through forced and unforced emigrations to North America and the antipodes, while India’s population was still burgeoning!

As a result, India was left tied to an outdated ‘low urban form’, strict zoning laws which militated against the poor, and development control rules (DCR) redolent of a past where the colonials lived in splendid bungalows, and the ‘natives’ lived in congested squalor. Remnants of this colonial past are still visible in the cantonment areas of cities like Pune, with crumbling bungalows (with empty stables!), huge tracts of vacant defence land, clubs (and even a racecourse!) occupying prime land in what could be the city’s Central Business District (CBD) if developed with an eye to the future instead of the past…

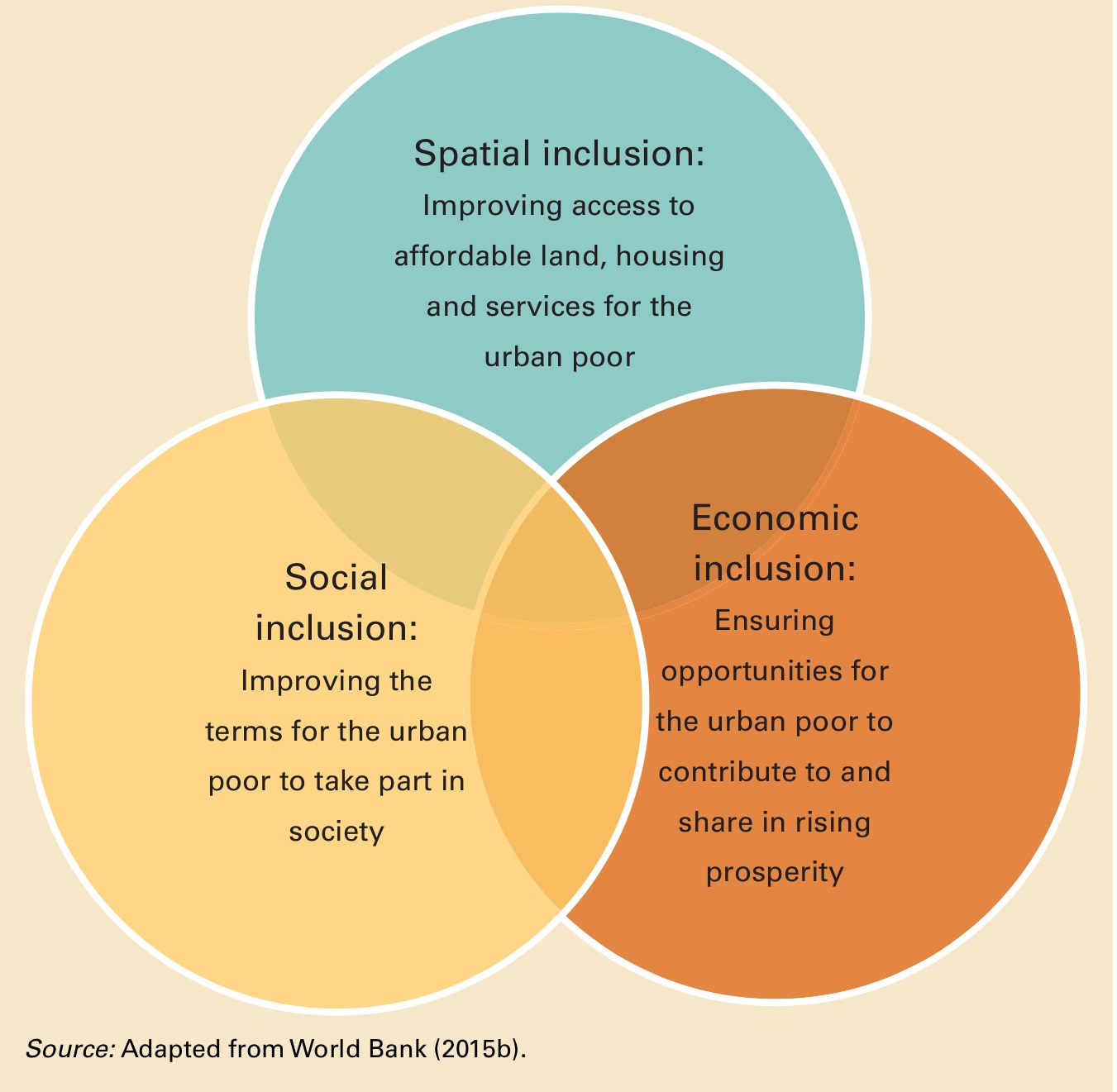

Streamlining and modernizing land laws is crucial to any urban planning that Indian cities may indulge in, and integrated, culturally relevant, flexible and people-friendly urban planning allows for less costly provision of basic services such as water and sanitation, higher resilience, climate change mitigation and adaptation, poverty reduction and pro-poor policies.

The cornerstone of current Indian urban planning is the Development Plan (DP), often described as the vision of the city, its physical configuration and growth in the foreseeable future, and the environmental considerations and technical solutions unique to the geography, history and social make-up of every city. It sets the agenda of what the city wants to do with itself in the next two to three decades. To make this vision a reality, the urban planner takes into account the various public requirements of the city and reserves lands, whether public or private, for those purposes. The plan also proposes conservation and preservation of areas that have natural, historical or architectural importance. The Development Plan also makes provisions for the city’s transportation and communication system such as roads, railways, airways and waterways, and parking facilities.

The two instruments of a Development Plan are zoning, and reservation:

- Zoning is the means whereby compatible land uses are grouped together, and incompatible uses segregated – such as manufacturing industry and residential areas.

- Reservations for public purposes include schools, colleges and educational institutions, medical and public health facilities, markets, social welfare and cultural institutions, theatres and places of public entertainment, religious buildings, burial grounds and crematoria, government buildings, open spaces and playgrounds, natural reserves and sanctuaries, dairies, sites for public utilities such as water supply and sewerage, fire stations, other community sites, service industries and industrial estates.

In order to successfully implement the Development Plan, the municipal body needs to be empowered and this is done through Development Control Rules (DCR). These rules deal with the manner in which building permission can be obtained, the general building requirements, and aspects of structural safety and services. Access, layouts, open spaces, area and height limitations, lifts, fire protection, exits and parking requirements are all stipulated in the DCR. Similarly, structural design, quality of material and workmanship, and inspections during construction are spelt out. The control of floor space use, tenement densities, and the Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) are some of the most crucial issues dealt with by these rules.

Although Development Planning is the path to city development all across the world, the sad fact is that in most Indian cities, not even 10% of a DP gets actually implemented. In fact, while all the tedious processes of approval, amendment and land acquisition are going on, the citizens have built their houses and moved in, without waiting for the infrastructure promised in the DP. Once an area becomes inhabited, the best a municipal body can do is retrofitting the essentials like water supply and sewerage, at huge cost. In this way are our ‘planned’ cities unplanned.

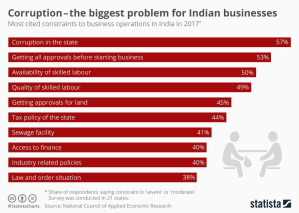

Urban Planning because of its control of that most precious commodity in an overcrowded country (land) is also susceptible to major subversion and scams. A well-documented case is that of the prime land tied up in Mumbai’s dead and dying textile mills, until the Supreme Court of India intervened to permit their brownfield redevelopment by the mill owners, with due reservations for public amenities and housing. The problem here arose from a little sleight of hand by vested interests. The Government of Maharashtra had introduced the Development Control Rules (DCR) in 1991, under which a mill owner was permitted to sell or redevelop his land, provided one-third was surrendered to the municipal corporation for public amenities and another third to the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) for low-cost housing. The remaining third was the owner’s. Ten years later, it surreptitiously amended this clause to make it apply only to vacant land – as distinct from the entire footprint of the mill. As a result, the first mill which would have surrendered 5,641 sq m for open space and 4,616 sq m to MHADA, got away with forfeiting just 474 sq m and 388 sq m respectively. In the case of Modern Mills, the corresponding figures are 8,626 versus 1,163 sq m as open space, and 7,058 sq m versus nothing for housing. Even this open space is often subsumed within the redeveloped complexes (mill to mall) and is not public space, strictly speaking.

This tendency to play fast and loose with planning laws and development control rules when it comes to big land owners in urban areas is deliberate, as it gives a lot of discretion to public officials and is the biggest source of corruption in local government. The ultimate losers, as always, are the unfortunate citizens of these cities, who keep getting pushed to the outer peripheries, as homes in the central areas have become simply unaffordable even for top earning professionals.

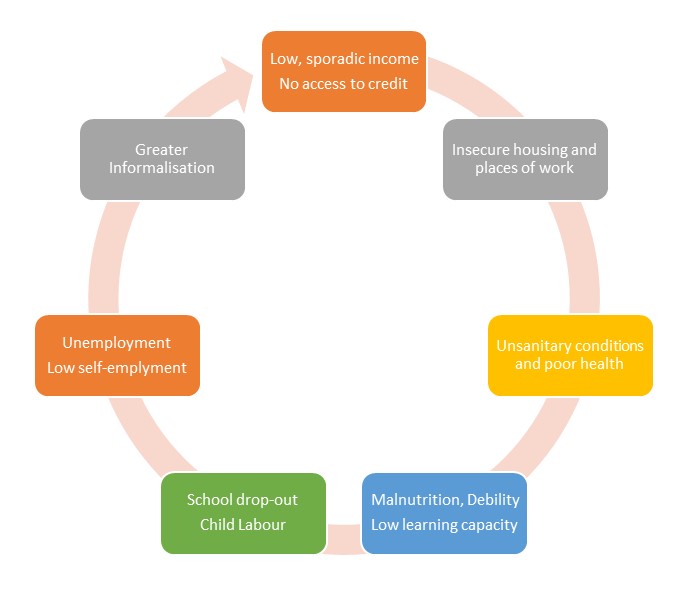

Lastly, when the very raison d’être of great cities has been manufacturing, how can they survive de-industrialization? They don’t. While de-industrialization may hollow out a western city, in India, de-industrialization ‘leaves the world to darkness and to me…’ The stalwart of the informal sector, living a life of quiet misery and departing life unmourned and unlamented. How and when will India reinvent its Bombays and Madrases? Perhaps by renaming them yet again?

According to UN Habitat, “…the city of the 21st century is one that transcends the form and functionality of previous models, balancing lower energy costs with a smaller ecological footprint, more compact form, and greater heterogeneity and functionality. This city safeguards against new risks and creates conditions for a higher provision of public goods, together with more creative spaces for imagination and social interaction.

The city of the 21st century is one that:

- Reduces disaster risks and vulnerabilities for all, including the poor, and builds resilience to any adverse forces of nature

- Stimulates local job creation, promotes social diversity, maintains a sustainable environment and recognizes the importance of public spaces

- Creates harmony between the five dimensions of prosperity and enhances the prospects for a better future

- Comes with a change of pace, profile and urban functions and provides the social, political and economic conditions of prosperity…”

Meanwhile, unchecked extraction by urban farmers and wealthy residents has caused groundwater levels to plunge to record lows, and the 21 major cities shown above, are expected to run out of groundwater by 2020, affecting 100 million people.

Meanwhile, unchecked extraction by urban farmers and wealthy residents has caused groundwater levels to plunge to record lows, and the 21 major cities shown above, are expected to run out of groundwater by 2020, affecting 100 million people.