Published in Times of India, Pune in October 2018. Lost and found. Posted here for you.

Very simply, large cities cannot be run as businesses because urban governance is more than just government. It is government + people. And while a business can clearly classify all its stakeholders (share-holders, management, workers, suppliers and distributors), how does a city draw the lines – between the property owners and the squatters? Between the tax-payers and the untaxed? Between the rich and the poor? Between the empowered citizens and the illegal migrants? Between the natives and the newcomers? Between the producers and the consumers? Between the governed and the government? Between local demands and regional priorities?

Thus, while a business can be satisfied with mere efficiency, a city needs to look at effectiveness. There is little merit in computerized property tax bills, if the tax base has not been updated for the last twenty years, is there? Ditto with completing a pumping station on time, if the water delivery continues to be erratic and unreliable. City dwellers are more interested in the water in their taps than in the technology which gets it there.

Similarly, a business doesn’t really care about participation, equity or inclusion while an urban government must necessarily provide for it.

Accountability in business is often merely a matter of financial accounting and compliance with various government norms – if they were accountable to society at large, we wouldn’t need a law of torts, or liability clauses in every business contract. A city on the other hand, is held to account in every election by its citizens, and there are a large number of mechanisms available today, for citizens to monitor and pull up their local governments.

These thoughts have come to mind as the citizens’ reactions to initiatives like AMRUT and Smart Cities are turning sour. Because they were (mis)led into believing that a little tweaking of software here, and a beautified road there would make them instantly more mobile and therefore more productive. That has not happened. Instead, the mistakes of the erstwhile government’s JNNURM have been repeated in duplicate, with private consultants running the show and the State and Local bodies who are expected to execute, complete and maintain the various infrastructure projects, sulking in the sidelines as before.

The fact that the JNNURM then, and AMRUT now, are deeply influenced by organizations like the ADB explains this ‘cities as businesses’ approach, where a Business Development Plan got renamed as a City Development Plan, and almost all reforms made mandatory, had a financial angle – and somewhere along the line we forgot what a mish-mash the urban scene in India is, with thousands of small market towns, ancient pilgrim towns, bustling cities, and dysfunctional megacities with huge informal sectors, all getting the same treatment.

Perhaps India needs to look at its BRICS partners for a lesson or two… Brazil had a similar experience, as the mayor of Sao Paulo admitted in an interview in 2013: “The previous economic model was very private-sector orientated, so the reaction of the local community was very negative. We need to rebalance the equation so development is not seen as a threat,” he said. “People consider politicians as bad people so it is important to get them involved personally. If they feel a sense of ownership then they don’t complain.”

So, the Brazilians took a different approach when preparing for the Olympics in Rio. They broadened the framework of a Smart City to include every aspect of the citizens’ lives: public safety, social programmes, healthcare, education, transportation, energy, water and the environment. And the tools used were smarter buildings and urban planning, and better government and agency administration. Only such a holistic approach which balances the human development, infrastructure and environmental aspects, and formulated with the active participation of the residents of a city, can make a city SMART in the long run.

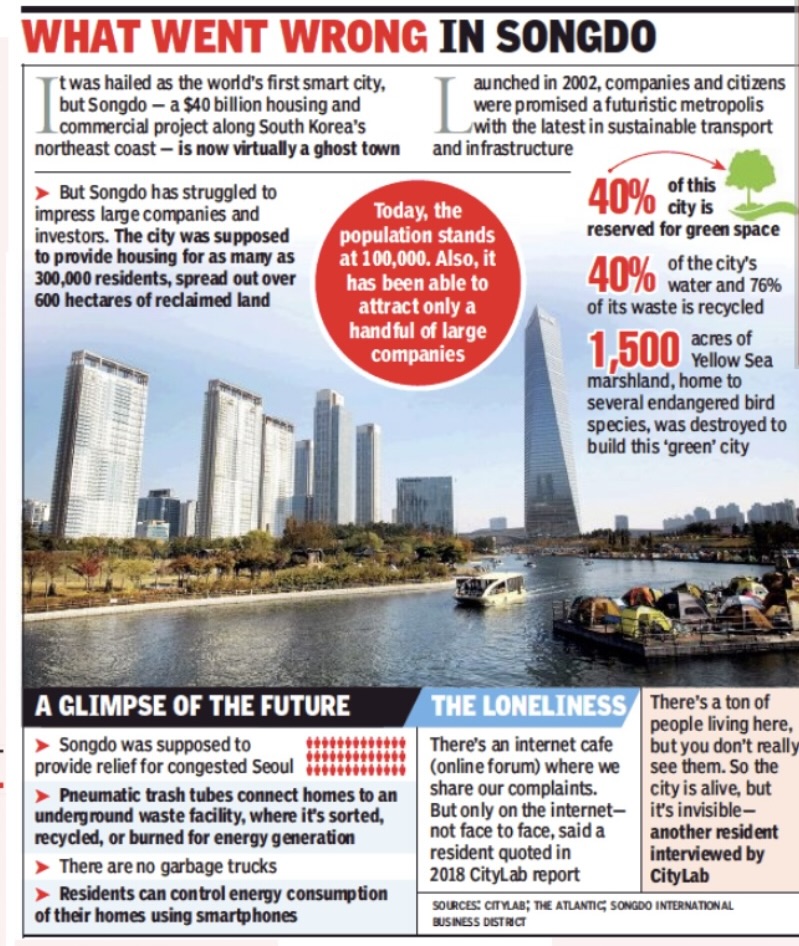

But who will convince the many IT consultants looking enviously at Songdo in South Korea or Masdar in the UAE, and hoping to create something similar in India? They don’t seem to realize that Indians may not really want this kind of super-efficient but impersonal urban experience. Nor that only a minute percentage could eventually afford to live in such a place!

Related: