Published in Times of India, Pune on 1 May 2019. Lost and found. Posted here for you.

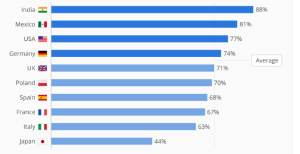

According to the latest World Bank estimates, the world generates 2.01 billion tonnes of municipal solid waste annually, and global waste is expected to grow to 3.40 billion tonnes by 2050. Worldwide, waste generated per person per day averages 0.74 kilogrammes, but ranges widely, from 0.11 in the poorest countries, to 4.54 kilogrammes in high-income countries – which generate about 34% of the world’s waste, although they only account for 16% of the world’s population.

Around the world, almost 40% of waste is disposed of in landfills. About 19% undergoes materials recovery through recycling and composting, and 11% is treated through modern incineration, while the remaining is openly dumped. More disturbing for the planet’s future is that at least 33% of the waste generated, is not managed in an environmentally safe manner.

The most common form of waste collection across the world, is door-to-door. In this model, trucks or small vehicles are used to pick up garbage outside of households at a predetermined frequency. In certain localities, communities may dispose off waste in a central container or collection point where it is picked up by the municipality and transported to final disposal sites. In lower-middle-income countries like India, collection rates are about 51%. Improvement of waste collection services is a critical step to reduce pollution and thereby to improve human health and longevity.

The city of Pune in Western India generates 1600 -1700 tons of solid waste per day, with 160 trucks deployed to collect waste door-to-door. In addition to household waste, the bulk generators are construction and demolition waste, garden waste, and biomedical waste.

Pune Region has set up 200 material recovery centres, to reduce, reuse, recycle and recover 170 to 180 MT of plastic waste it generates per day, but 10,000 MT of e-waste per annum continues to pose a challenge. The downside of a green and beautiful Pune, is of course the huge quantities of garden waste generated – 60 to 70 MT per day – and a separate collection system is in place for collecting the waste, shredding it and transporting it to a centralised processing system.

Waste disposal practices vary significantly by income level and region, and as nations prosper economically, waste is managed using more sustainable methods. Construction and use of landfills, is commonly the first step toward sustainable waste management.

The darker side of waste disposal is that richer countries often export their electronic waste to poorer countries and this e-waste contains toxic substances such as lead, mercury, cadmium, arsenic and flame retardants. Once in a landfill, these toxic materials seep out into the environment, contaminating land, water and the air, and harming the local community. In addition, devices are often dismantled in primitive conditions, and those who work at these sites suffer frequent bouts of illness, and long-term diseases.

The ship-breaking yard at Alang in Gujarat is notorious for the chronic illnesses of its workforce, and is sardonically referred to as ‘Alang se Palang’ – death bed. On-site medical facilities at such places are either absent or totally inadequate.

The South Asia Region, where India is the largest country, generated 334 million tonnes of waste in 2016, at an average of 0.52 kilogram per capita daily, with 57% characterized as food and green waste. About 44% of waste is collected in South Asia, mainly through door-to-door systems, and three-fourths of waste is currently openly dumped, although improvements to collection systems and construction of sanitary final disposal sites are under way.

It is estimated that basic solid waste management systems covering collection, transport, and sanitary disposal in low-income countries cost $35 per tonne at a minimum, and often much more. Systems that include more advanced approaches for waste treatment and recycling, naturally cost more – from $50 to $100 per tonne.

Almost all low-income countries, and a limited number of high-income countries, such as the Republic of Korea and Japan, subsidize domestic waste management from national or local budgets. The PMC sets aside 20.5% of Annual Rateable Value of one’s property as Conservancy Tax, in your annual property tax bill. Given that the base figure itself is often a gross undervaluation and seldom updated and all property taxes are non-buoyant, this amount is totally inadequate to cover the ever-rising costs of labour, transport, treatment and disposal. As a result, the local government has to depend on State and Central Government subsidies, and as with any subsidized service, the customer is never satisfied with the quality and adequacy of service provided.

Although public-private partnerships could potentially reduce the burden on local government budgets, the experience of such services in Indian cities has not been very encouraging.

Thus, we are basically left with three options and some tough choices, if our cities are not to disappear in mounds of garbage:

- Increase Fee collection – a move sure to meet with great resistance

- Strengthen household waste collection systems by active collaboration of both the waste generators (at the housing society level), and NGOs or Collectives of professional waste collectors

- Decentralize the waste collection, treatment and disposal systems to Ward level.

Related: