It is estimated that to break out of the present poverty-pollution-population trap, India needs to create some one hundred million sustainable livelihoods in the next ten years, to cover the backlog, plus a similar number for the new entrants into the job market. With this many jobs created, each family in the country can hope to have at least one member with a reasonably paid job.

Given the present direction in both the public and corporate sectors, it is expected that not even 10% of this target will be met. With the new Government’s Make in India emphasis on further industrialisation, any jobs created will be in the formal sector and for non-poor households. True, there will be some trickle down through outsourcing, but as this sub-contracting will only be in India’s urban informal sector, it is not likely to provide long-term, sustainable livelihoods, nor build up the coping mechanisms of the poor.

What do we mean by Sustainable Livelihoods?

As we have seen in an earlier post, urban poverty is a complex multi-dimensional phenomenon, and therefore the approaches to poverty reduction must also be multi-dimensional. Current thinking in development studies has seen a paradigm shift from top-down planning to participatory micro planning, with the focus on local people and their livelihood strategies. There is also a concerted effort to make people aware of their rights and entitlements, so that priorities are fixed by the people rather than by a faceless bureaucracy.

One such approach, developed initially for rural areas and now successfully adapted to urban areas is the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF).

The SL framework revolves around three assessment criteria:

Foremost of them is the ASSETS or CAPITAL of the individual or community. Assets may be financial, natural, human, social or physical as detailed later.

The second criterion is the RIGHTS and ENTITLEMENTS available to the community or individual. These may be traditional, social, moral, legal, or political. Entitlements are things that people may rely upon because of legal or customary rights – like access to common-property resources, employment benefits, right of usufruct on land etc. Entitlements could also include the mutual support structures that are often present in localized communities.

And the final criterion is how far ACTIVITIES dovetail with assets and entitlements. Activities are things that people do to gain a living, and these will usually be based on available assets. A personal asset, such as artistic ability, may form the basis of activities that generate income. Land may be used to earn income. Activities may be based on acquired knowledge and skills; thus education and training has a prominent position in a sustainable livelihoods framework. Knowledge and skills may also be acquired through traditional, cultural processes.

Sometimes, a fourth criterion is added to assess how successfully the individual or group can deal with the vulnerabilities and risks of their situation, and how well they can come up with a COPING STRATEGY.

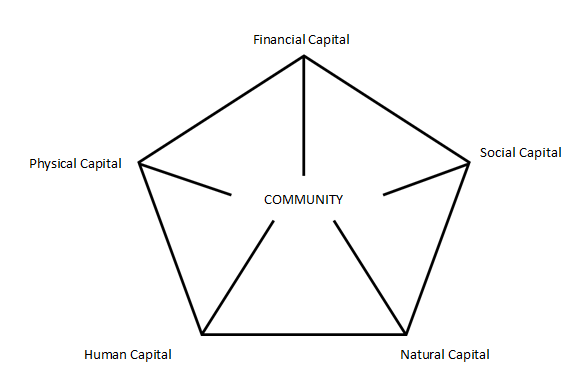

The SL Framework defines five types of Capital Assets. These are:

Financial Capital which denotes financial resources like: wages, salaries, pension, savings, access to credit, rent, remittances and so on.

Physical Capital or basic infrastructure facilities like roads, transport, electricity, water supply, energy, communication, tools and technology for production

Natural Capital like food security, adequate water supply, minimum air and noise pollution

Human Capital through skills, knowledge, good health, ability to work

Social Capital which includes the formal and informal social relationships such as kinship ties, client-patron relationships, networks and organisations that exist in a community

Under the sustainable livelihood framework it is possible to draw a livelihood polygon for an individual, a group or a community, as illustrated below:

The relative length of each of the arrows connecting to the corners of the polygon, is an indicator of the adequacy/ inadequacy of a particular type of capital in a particular community. In the above case, if all assets or capitals are adequately developed, we see a larger polygon, thereby providing greater livelihood opportunities, and stronger coping abilities to individuals/communities.

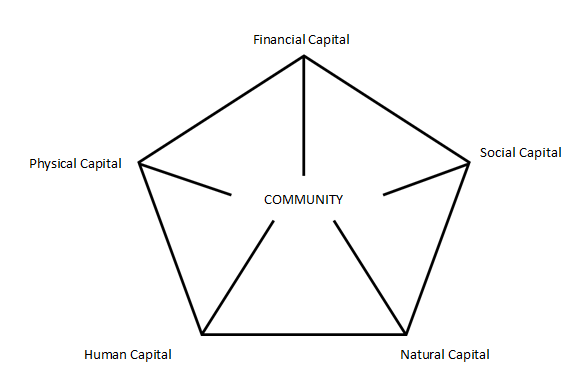

However, most government programmes tend to focus on just one type of capital/asset, thereby greatly shrinking the options available to the poor. For example, slum upgradation programmes in India concentrate on providing only physical infrastructure like internal roads, storm drains, public water and sanitation, and neglect the growth of human capital through better health and education services. This results in a skewed livelihood polygon with a much smaller area of opportunity for the individual and community, as shown below:

The SL Framework in Urban Areas

The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) can be used in the urban context to assess the current state of assets/capital in a community, and then plan new poverty reduction strategies based on this assessment. In fact, it is the ideal framework for undertaking a City Poverty Profile. Practical solutions can then be worked out within the available resources to maximise each of the five ASSETS or CAPITALS in the community, so that the livelihood polygon of the community can be suitably expanded. It must be remembered that every decision may affect more than one type of capital, sometimes adversely. The emphasis is therefore on thinking holistically and getting the balance right.

Thus, FINANCIAL CAPITAL can be greatly augmented through: Providing a place for a cooperative store / fair price shop to be run by the community; starting kitchen gardens; installing metered electricity connections in each household; forming women’s Self Help Groups; setting up labour cooperatives; and providing vocational training geared to local handicrafts / industry.

NATURAL CAPITAL can be enhanced by easy ‘doables’ like providing a playground for children near their homes, initiating participatory activities for improving community environment and sanitation, and providing the means for rainwater harvesting.

The growth of HUMAN CAPITAL in a community is a combination of sound health, education, skill development and capacity to work. All countries have numerous human development programmes either initiated by donor agencies, through NGOs, or undertaken by Governments themselves. Some of these which have impacted positively on HD across the world include: regular antenatal and post natal check-ups by community health workers; regular check-ups for HIV/AIDS, STD; Gender budgeting; immunization camps; mobile clinic schemes; improved housing and sanitation; night classes for school dropouts / child labourers; women’s Self Help Groups; nutrition checks on under-5 children on a monthly basis, awareness campaigns against drug addiction, alcoholism, domestic violence; increasing the number of group connections for water supply, adult literacy classes; school attendance / drop outs to be monitored by the community itself; constructing / upgrading community toilets for washing, bathing facilities for women… and many more

PHYSICAL CAPITAL is already the only focus of slum improvement programmes in India, but remains very narrow in its ambit. It should also look to augment infrastructure that will help enhance other assets like income, health and education by, for example, transforming muddy approach roads to all-weather roads, building / upgrading community health and family planning centres, improving the housing facilities, removing encroachments, providing covered drains and sanitary facilities, etc.

It is often said that SOCIAL CAPITAL is the only wealth of the poor Indian, given the vast array of caste, clan, ethnic, linguistic, tribal and kinship networks in rural India. These ties, however, are the first casualty, when the rural poor migrate to the cities. However, it is possible through development interventions to build new networks and support systems – the most obvious examples being Self Help Groups, Thrift Societies, and Workers’ Cooperatives. Group activities like literacy drives, mass immunization campaigns, and nutritional assessment camps are also instrumental in cementing community bonds, besides helping with human capital growth.

So where do we go from here? Experts believe that the answer lies in small scale, decentralised industries of a new kind. The key factor is the application of new technologies to the traditional skill and resource base of the community. For instance, the traditional knowledge of certain tribal communities can be successfully utilised in wildlife tourism, and its conservation and preservation. Similarly, with urban heritage suddenly becoming a priority in India, there is a lot of scope for traditional artisans in restoration and preservation of heritage buildings.

If the traditional knowledge handed down from generation to generation is not correctly utilised, it will be lost forever, and will have to be rediscovered and relearnt in Universities (as in Europe), thereby becoming an asset not of the poor – its original owners – but the better off.

Should we sleepwalk through yet another cycle of deprivation, or hear the wake-up call?

Perhaps, the Kudumbashree Programme of the Kerala Government could point the way to sustainable livelihoods for the entire country. They deserve an entire post to themselves, which I shall hope to put up soon. Meanwhile, time for a diversion don’t you think?

Interestingly, we were told that because of the single child norm, the gender ratio in Shanghai is so skewed, that the typical, treasured Shanghai girl can pick and choose the husband she likes, one who most fulfils her many demands. And remains a good and faithful husband all his life!

Interestingly, we were told that because of the single child norm, the gender ratio in Shanghai is so skewed, that the typical, treasured Shanghai girl can pick and choose the husband she likes, one who most fulfils her many demands. And remains a good and faithful husband all his life!